Social Structure

Greater kudus live in clans—bonded social groups of about seven to ten individuals. These groups consist of adult females, juveniles, the very young, and adult males less than two years old. At age two, males leave the clan and live either in pairs or in groups led by older adult males. Dominance ranking between males is based on age; males emphasize their size by hunching their backs and raising their manes, but will not engage in sparring unless the other male is equal in size. Older females do not participate in dominance ranking. Females tend to remain in their mother’s clan, though clans will split if the group grows too large. When this occurs, the home range is divided between groups. Some groups of kudus follow a leader—usually an older male—who moves on his own but is trailed by the rest of the clan.

Communication

With excellent vision and hearing, greater kudus communicate mostly through sight and sound. Scent is also useful; kudus can track other individuals over long distances by following their scent trails. Body signals, such as flashing the white undersides of their tails, are used to indicate the movements and presence of predators. Kudus will emit a loud bark to warn others of danger, but otherwise are not very vocal. Most communication occurs between members of a particular social group; different clans usually ignore one another even when they are together.

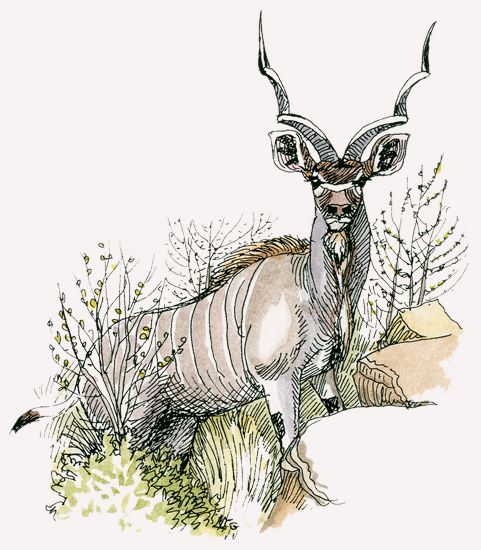

Behavior

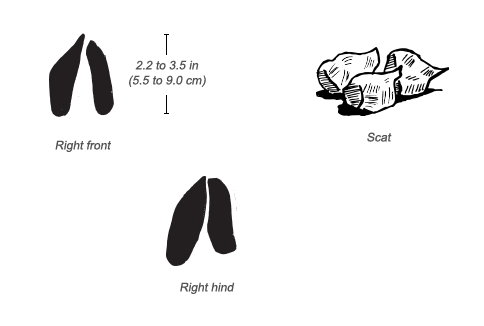

Greater kudu forage in the early morning and again in the late afternoon and into the evening, spending an estimated 63 percent of their day and about half of their night just eating. Right before dawn, kudus curl up on the ground to rest. To determine dominance, males spar playfully. If the males are comparable in size, they lock horns and push or twist against each other. On rare occasions, their spiraling horns become so entangled that the males become trapped together—and eventually die.

Conservation

With striking horns and good meat, greater kudus seem an ideal target for hunters, but their populations have proven resistant to poaching. This is likely due to their cautious and elusive behavior. Furthermore, farmers and ranchers do not mind their presence because they do not compete with livestock for food. Living close to ranches can be problematic for kudus because they are susceptible to diseases that cattle contract.